Leveraging machine learning to uncover the lives and deaths of massive stars

Observations of merging binary black hole systems allow us to probe the behavior of matter under extreme temperatures and pressures, the cosmic expansion rate of the Universe, and the fundamental nature of gravity. The precision with which we can extract this information is limited by the number of observed sources; the more systems we observe, the more we can learn about astrophysics and cosmology. However, as the precision of our measurements increases it becomes increasingly important to interrogate sources of bias intrinsic to our analysis methods. Given the number of sources we expect to observe in the coming years, we will need radically new analysis methods to avoid becoming dominated by sources of systematic bias. By combining physical knowledge of the observed systems and AI methods, we can overcome these challenges and face the oncoming tide of observations.

A New Window on the Universe

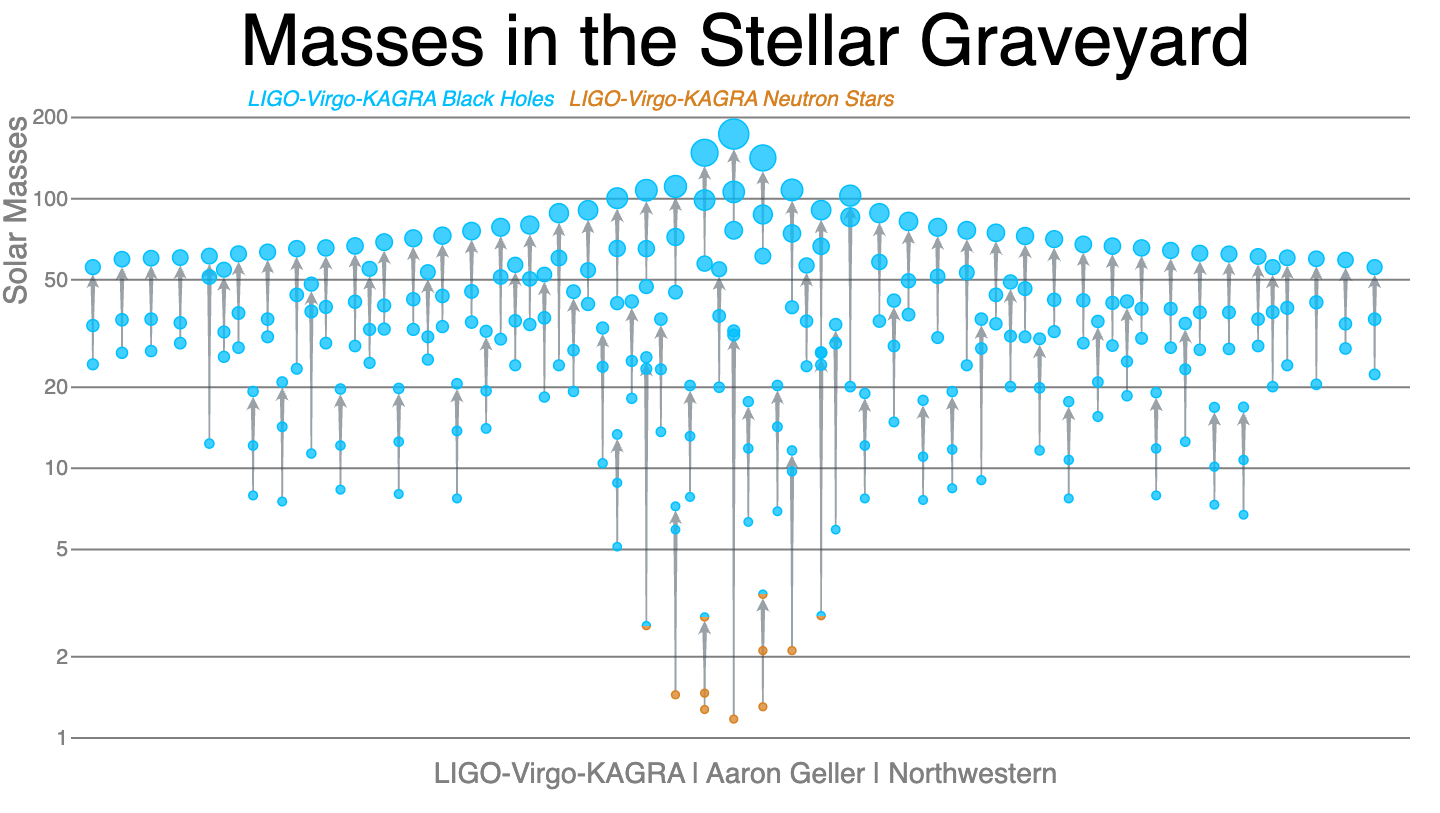

In September 2015, a new field of astronomy was born with the observation of gravitational waves from the collision of two black holes over a billion light years away by the twin LIGO detectors. In the intervening years, the LIGO detectors have been joined by the Virgo detector and similar signals have been observed from over 100 additional merging binaries. Despite this large and growing number of observations, many more signals are not resolvable by current detectors due to observational selection bias. An example of this selection bias is that more massive binaries radiate more than less massive binaries and so are observable at greater distances. Over the next decade, upgrades to existing instruments will increase our sensitivity and increase the observed catalog to many hundreds by the end of the decade. In addition, the planned next generation of detectors is expected to observe every binary black hole merger in the Universe, accumulating a new binary every few minutes.

Each of these mergers is the end of an evolutionary path from pairs of stars initially more tens of times massive than the Sun. Over their lives, these stars passed through a complex series of evolutionary phases and interactions with their companion star. This path includes extended periods of steady mass loss during the lifetime of the star, dramatic mass loss during a supernova explosion, and mass transfer between the two stars. Each of these effects is determined by currently unknown physics. Understanding the physical processes governing this evolutionary path is a key goal of gravitational-wave astronomy.

From Data to Astrophysics

Extracting this information requires performing a simultaneous analysis of all of the observed signals while accounting for the observation bias. Individual events are characterized by assuming that the instrumental noise around the time of the merger is well understood. The observation bias is characterized by adding simulated signals to the observed data and counting what fraction of these signals are recovered. In practice, the population analysis is performed using a multi-stage framework where the individual observations and the observation bias are analyzed with an initial simple model and then combined using physically-motivated models.

Using this approach we have learned that: black holes between twenty and a hundred times the mass of the Sun exist and merge; a previously unobserved population. there is an excess of black holes approximately 35 times the mass of the Sun implying there is a characteristic mass scale to the processes of stellar evolution. most merging black holes rotate slowly, in contrast to black holes observed in the Milky Way.

Growing Pains

Previous research has shown that AI methods can solve gravitational-wave data analysis problems, in some cases far more efficiently than classical methods. However, these methods also struggle to deal with the large volume of data that will be available in the coming years. As a Schmidt fellow, I am working to combine theoretical knowledge about the signals we observe with simulation-based inference methods to overcome this limitation and allow us to leverage the growing catalog of binary black hole mergers fully.

For example, while the statistical uncertainty in our inference decreases as the catalog grows, the systematic error intrinsic to our analysis method grows approximately quadratically with the size of the observed population. This systematic error is driven by the method used to account for the observational bias. In previous work, I demonstrated that by reformulating our analysis as a density estimation problem we can reduce this systematic error, however, this is simply a band-aid and not a full solution.

I am currently working on using approximate Bayesian computation to analyze large sets of observations in a way that is less susceptible to systematic error. An open question in how to perform such analyses is how to efficiently represent the large volume of observed data. I am exploring how we can use theoretically motivated pre-processing stages to avoid the need for large embedding networks that are traditionally used. By combining this theoretical understanding of the problem with AI methods I hope to extract astrophysical insights from gravitational-wave observations with both more robustness and reduced computational cost.

This work was funded by the Eric and Wendy Schmidt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Program of Schmidt Futures and originally published here.